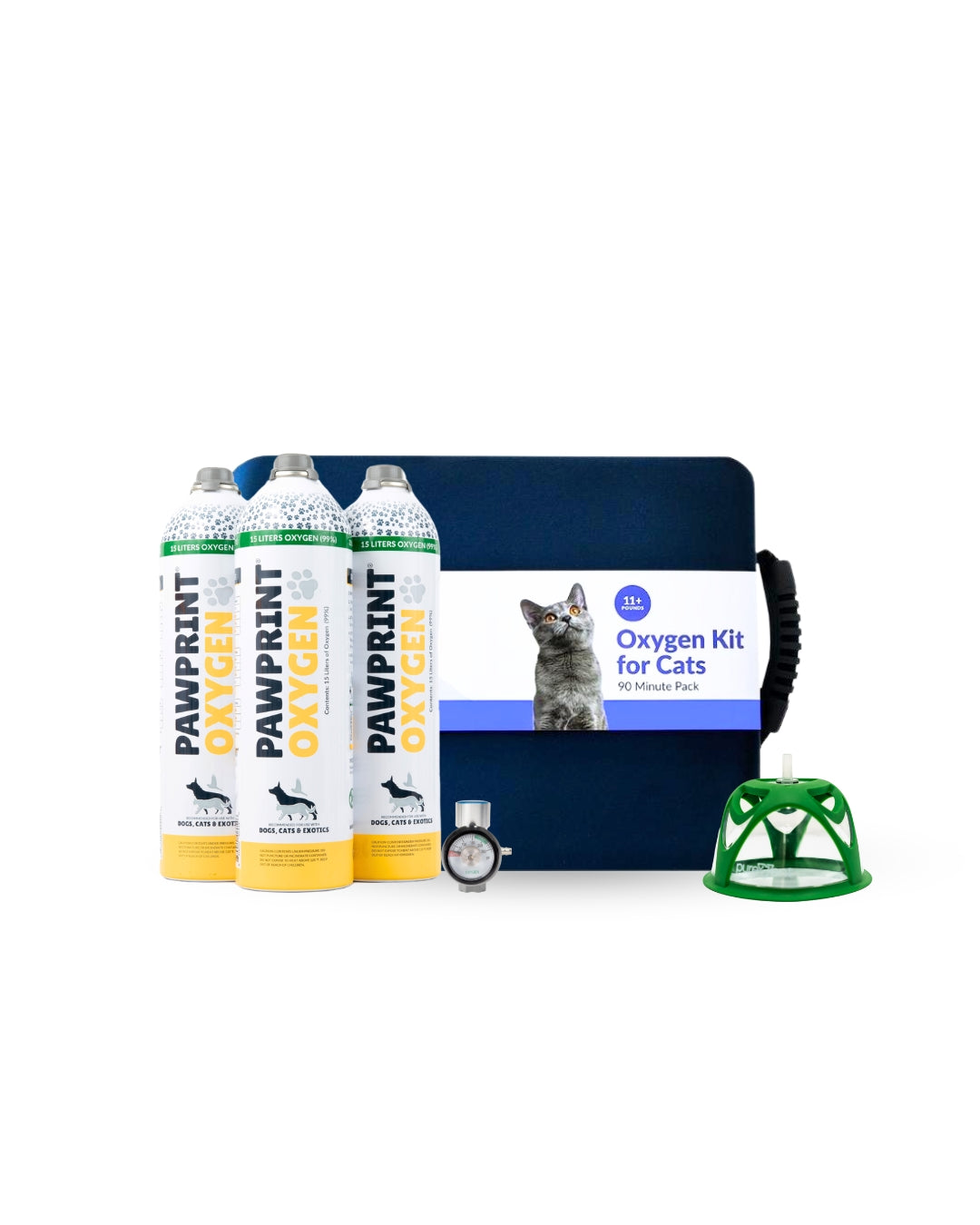

The Pet Oxygen Mask is the most practical option for at- home use. It is available in three different sizes to accommodate the patient’s snout and is exceptionally easy for pet parents to use. The rubber diaphragm is usually removed to increase patient acceptance, decrease breathing resistance and prevent rebreathing unless the size of the patient and gas flow justify their use. Veterinary hospitals can employ alternative oxygen administration devices depending on the pet parent, patient and condition, and the possible use scenarios, such as during transfer or at-home use.

In addition to masks, oxygen adminstration E-collars are commercially available or can be created by using plastic cling wrap covering 80% of the ventral opening1 with the tube entering at the collar. The recommended flow rates to achieve desired oxygen supplementation and avoid rebreathing are 200ml/kg/min for a mask and 100ml/kg/min for a vented e-collar2 The actual FiO2 obtained is dependent on:

1) The minute volume (how much air the patient is moving in and out of their lungs per minute)

2) The space of the device and other dead space

3) Venting and entrainment from the device

4) The oxygen flow rate.3

One of the most efficient methods for administering oxygen to veterinary patients is the nasal (pharyngeal) catheter which provides an FiO2 of approximately 30% at 50 ml/kg/min via single catheter ranging to 60% at 100ml/kg/min with via double catheter3, 4 Due to their length, catheters provide a higher FiO2 at a lower flow rate and are better tolerated than human nasal cannulas. Nasal (pharyngeal) catheterization is an easy and cost-effective procedure:

1) Premeasure a red rubber or commercially available specific catheter so that it occupies 1/3 to ½ of the diameter of the nostril and spans from the nostril opening to the to the lateral canthus of the eye.

2) Instill proparacaine into the nostril; the nose is pushed dorsal while the catheter is aimed ventrally to assure placement into the ventral (largest) meatus. Passage is accommodated with the use of lidocaine jelly or water based lubricant.

3) Once the catheter is advanced to the pre-measured length (stop if resistance is encountered and reattempt), place a tape or other butterfly on the catheter just caudal and slightly ventral to the nostril and suture or staple it to the muzzle.

4) Secure the catheter on the side of the face/head or up the middle of the face and on top of the head.

Nasal (pharyngeal) catheterization is recommended for transporting medium to large dogs.

Any time oxygen is administered in a way that encloses the mouth (mask), head (e-collar) , or patient (oxygen cage), overheating and additional anxiety to the patient must be avoided. If a mask is not feasible, other administration options can be considered. Most pet parents report their pets calm down after the mask is applied and kept in place for a minute or so as the hypoxemia is addressed.

About Sean Smarick, VMD, DACVECC

Dr. Sean Smarick received his Doctor of Veterinary Medicine from the University of Pennsylvania in 1991. He then completed a residency in Veterinary Small Animal Emergency and Critical Care at the University of California, Davis in 2003 and, in the same year, became a Diplomat of the American College of Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care. In his 30 years of practice, Dr Smarick has enjoyed being in the ICU and emergency rooms of private and university practices, participating in CPR and clinical research, contributing to journals and textbooks, training residents and interns, and serving on the board of several veterinary businesses and organizations. Dr. Smarick currently serves as the Post-Cardiac Arrest Care Domian Chair of RECOVER , as a Trustee on the Board of the PVMA , and as a commissioned Veterinary Corps Officer in the US Army Reserves. In addition to providing local and national instruction to handlers, paramedics and veterinarians, he is involved in pre-hospital veterinary care as a member of the VetCOT ATLS and education committees, the K9 TECC working group , and on the board of NAVEMS.