Veterinarians Using Transport Rescue Oxygen For Pets

While we consider the at-home emergency use of beta agonists (inhaled or injectable) for cats with feline asthma1 and (rectal or intranasal) administration of benzodiazepines for seizing dogs 2 to be standard of care, this was not the case just a decade or two ago.

I can remember from my early practice days the advice that was given to apprehensive pet parents concerned about recurrence was simply “See a veterinarian immediately.” Such advice was in denial of its obvious shortcomings: until the pet’s return in critical condition or worse.

Such at-home interventions supported the patients until they were able to reach the veterinary hospital and, in many cases, eliminated the need for an emergency visit all together by interrupting the vicious cycle of respiratory distress or cluster seizures.3

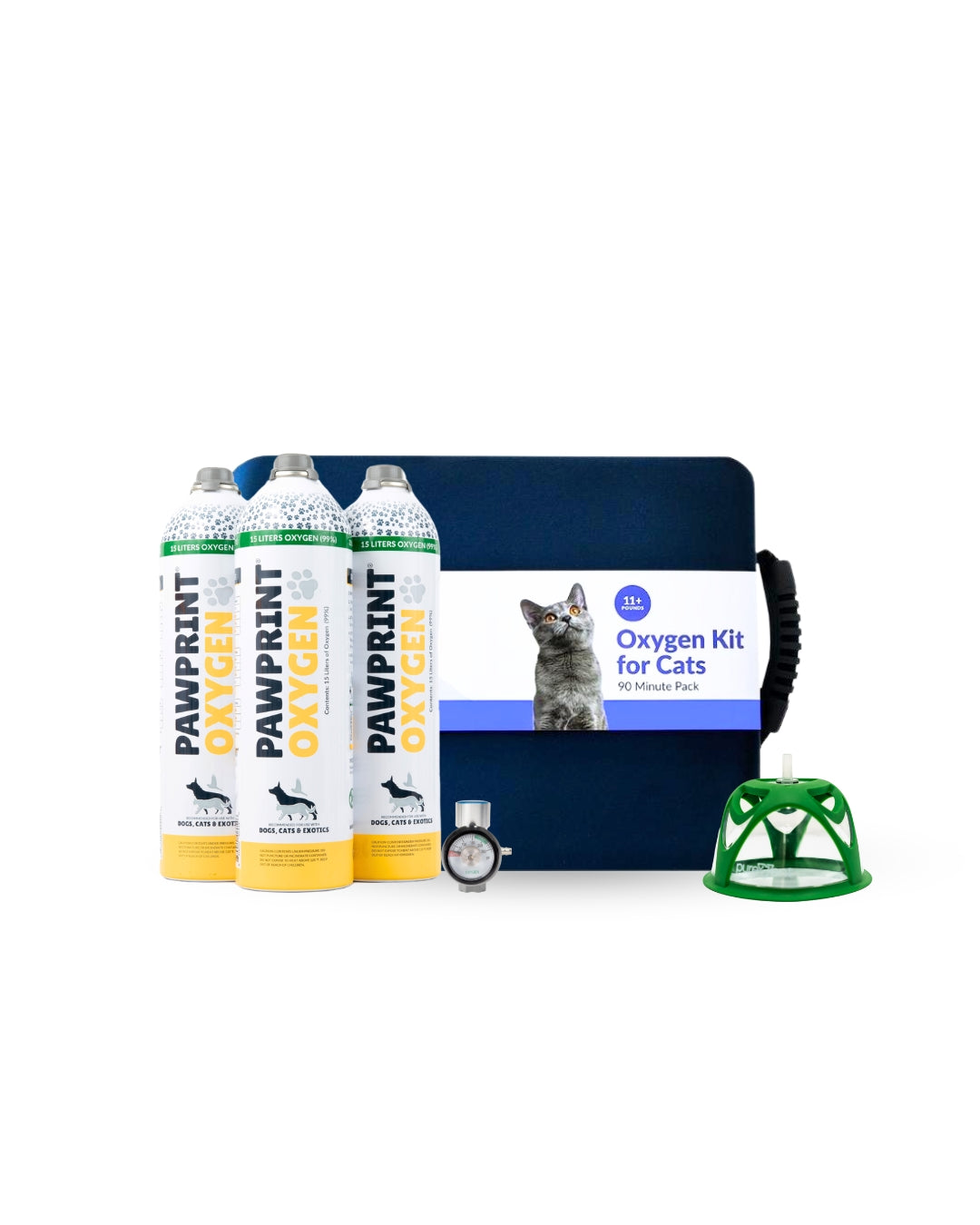

Dog Oxygen Rescue Kit

Our Oxygen Rescue Kits are designed to help your dog exactly when they need it. You can administer on-the-spot oxygen or oxygen in transport while on your way to emergency care. Dogs needing this rescue kit would likely suffer from more acute health conditions like seizures or be in a high-risk category that you'd like to keep a kit on hand to transport them with.

We use echocardiography, board-certified cardiologists and a plethora of medications to manage heart failure patients, yet we are still giving the same advice from decades ago for patients that decompensate at home into pulmonary edema leading to hypoxemia and respiratory distress: “See a veterinarian immediately!” This is not a comforting message to a pet parent who never wants to see their pet struggle to breathe on the way to the hospital and is just hoping that they will make it in time. It is said that “hope” should not be one’s sole strategy!

It is not only the patient in congestive heart failure (CHF) that risks decompensation leading to hypoxemia, respiratory distress, and even death. Conditions such as collapsing trachea, brachycephalic airway syndrome, laryngeal paralysis, feline asthma or lower airway disease and chronic pulmonary conditions can be treated but often not cured, leading to inevitable decompensation and respiratory distress. The pet parent and veterinarian should therefore be prepared for “when” not “if” this transpires.

When such patients decompensate, the resulting hypoxemia often creates a vicious cycle of increased work of breathing leading to increased oxygen needs, thus exacerbating the hypoxemia.This physiology does not change at home vs. in the hospital -- oxygen is the first line of treatment and conveys its effects immediately.

Like the rescue beta agonist or benzodiazepine, which can prevent an emergency visit, home oxygen may interrupt the vicious cycle frequently seen in conditions with dynamic obstructions such as laryngeal paralysis, collapsing trachea and brachycephalic syndromes along with feline asthma. Oxygen therapy can help to support pets with these conditions, as well as other conditions during transport to definitive veterinary care.

About Sean Smarick, VMD, DACVECC

Dr. Sean Smarick received his Doctor of Veterinary Medicine from the University of Pennsylvania in 1991. He then completed a residency in Veterinary Small Animal Emergency and Critical Care at the University of California, Davis in 2003 and, in the same year, became a Diplomat of the American College of Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care. In his 30 years of practice, Dr Smarick has enjoyed being in the ICU and emergency rooms of private and university practices, participating in CPR and clinical research, contributing to journals and textbooks, training residents and interns, and serving on the board of several veterinary businesses and organizations. Dr. Smarick currently serves as the Post-Cardiac Arrest Care Domian Chair of RECOVER , as a Trustee on the Board of the PVMA , and as a commissioned Veterinary Corps Officer in the US Army Reserves. In addition to providing local and national instruction to handlers, paramedics and veterinarians, he is involved in pre-hospital veterinary care as a member of the VetCOT ATLS and education committees, the K9 TECC working group , and on the board of NAVEMS.

Sources:

1. Trzil, J (2020), Feline Asthma Diagnostic and Treatment Update. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2020;50(2):375-391.doi:10.1016/j.cvsm.2019.10.002 2. Charalambous, M., Bhatti, S., Van Ham, L., Platt, S., Jeffery, N., Tipold, A., Siedenburg, J., Volk, H., Hasegawa, D., Gallucci, A., Gandini, G., Musteata, M., Ives, E. and Vanhaesebrouck, A. (2017), Intranasal Midazolam versus Rectal Diazepam for the Management of Canine Status Epilepticus: A Multicenter Randomized Parallel‐Group Clinical Trial. J Vet Intern Med, 31: 1149-1158. doi:10.1111/jvim.14734 3. Podell, M. (1995), The Use of Diazepam Per Rectum at Home for the Acute Management of Cluster Seizures in Dogs. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 9: 68-74. doi:10.1111/j.1939-1676.1995.tb03275.x